Bullets, blood and the saviour that was Phil Martin

THERE was a bullet-proof vest on one of the hangers in the changing room at the gym Phil Martin built in Moss Side. It was 1993 and the streets outside were the bloodiest in Britain.

Martin had found the building after the burning and destruction of the riots in 1981. It was a smouldering ruin when Martin found it. He made the impossible happen and shaped a world-class gym from the debris. It was his place; those were his streets.

He had the vision for change, he was a respected man, a dreamer in many ways. He had been an amateur boxer, a professional fighter, a car mechanic, union organiser, a simple working man.

As a pro, he beat Frankie Lucas and in 1975 he outpointed Johnny Frankham, just a few weeks after Frankham had lost the British title to Chris Finnegan.

In 1976, Martin lost a British light-heavyweight title fight to Tim Wood over the full 15-round distance. Harold Wilson and Edward Heath were the ringside guests that night at the Grosvenor House in London’s Park Lane. There was a loss to Bunny Johnson and then, in 1978, Martin walked away from the sport with 14 wins and six defeats. He was not finished with boxing.

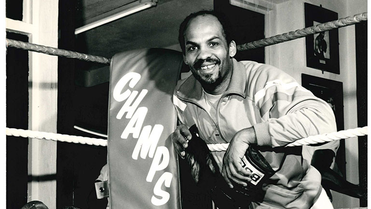

Martin had to beg and borrow to get the gym built, painted and open. He called it Champs Camp and it was one of the few beacons of hope in a part of a city that was being ignored.

On the wall outside there was a giant mural of Muhammad Ali. It was from a Neil Leifer picture, taken at the 1965 fight with Sonny Liston – the one where Ali is telling Liston to get up. That was the perfect Ali image to look down on a damaged city, a face full of anger and pride – a place full of anger and pride.

It was a long journey for Martin and his boys and men. They soon became familiar on the amateur scene and then feared; then they took on the professionals. Martin had a reputation; he had several reputations.

He helped establish an identity to a lost part of Manchester and delivered British champions and attracted the right type of attention. At one point in 1993 he had four British champions in the gym.

In 1993 there were over 100 shooting incidents in Moss Side.

Paul Burke, Maurice Core, Frank Grant and Carl Thompson were Martin’s men, British champions with their pictures in the paper; the quartet all smiling and holding their Lonsdale Belts. That was a revolution in Moss Side and Phil Martin believed in a revolution.

Martin was not universally loved. Times were tough, man, and boxing coverage was a bit lean and still a bit old-school. At one of his shows in 1993, which took place on a Sunday in Oldham, the four British champions boxed and another of his men was fighting for the British title. That’s some achievement; no television, obviously.

Steve Walker lost for the British super-featherweight title; Thompson, Core, Burke and Grant won. Eric Noi and Steve Foster also won. And iconic American journeymen – real boxing journeymen – Willie Jake and Randy Smith put on display their skills. The pair met about 30 world champions during their careers. Mario Culpepper won for the fourth time; Culpepper might have been the owner of the bullet-proof vest I had seen in the gym a few weeks earlier. Will there ever be another independent show like that?

Steve Lillis was there for the Sport; Steve was Martin’s great backer from before the glory days. It was a mad afternoon. I think I got 200 words in the paper.

Phil Martin died in April of 1994, now one of British boxing’s forgotten men.

He left behind his methods, his teachings and his memories. There are now a lot of glorious Martin myths about the boxers and men and killers and other refugees from the streets who found sanctuary up his stairs in Champs Camp.

Martin made Billy Graham and Joe Gallagher and gave them his code. They fought next to him, worked with him. On the other side of Manchester, another boxing guru, Brian Hughes, was making his own men in his image. Two human giants saving souls in their Manchester boxing gyms.

I once referred to Martin’s code as a “science of decency.” He could reject a politician’s hand of peace and embrace the bloody paw of a bad kid with a fresh wound. He did both on a regular basis.

It was in 1993 that Chris Eubank, WBO champion at the time, arrived at the gym and arrived in Moss Side. Eubank had a cousin who fought for Martin. It was a hostile time, a dangerous time.

A kid called Benji Stanley, just 14, had been blasted by a shotgun at Alvino’s Pattie and Dumplin’ Shop. The shop was just metres from the gym entrance. Eubank arrived for his tour, his peace mission and I have always been convinced he had the best intentions. I was with him. There was a march to keep the Stanley story active, Core was part of the march and so was Eubank.

Eubank went to the gym to meet Martin. It never went well; Martin was not moved by a photo opportunity. It is a pity because they could have done some good working together.

“I have been here for 20 years, he’s been here 20 minutes and he’s getting all the publicity,” Martin told me just minutes after Eubank had left the gym. “I was listening to him go on and I just told him to shut up and f**k off. I’d heard enough.” The Eubank tour was over.

“He gave everybody a chance,” Core told me. Martin and Core were close, he was one of Martin’s special projects. Core was also held in Strangeways on nine attempted murder charges.

“Nine, can you believe it? Nine.” He was cleared and compensated.

Core keeps the memories alive; he became a school governor and helped keep the gym open and still keeps the peace. “Even now in Moss Side, everybody has a Phil story,” Core told me. Many have a Maurice Core story. It was left to Core to deliver testimony at the death service.

A newspaper reporter called Jim Bentley was also on the scene then. Now, Bentley is the senior producer for the boxing on DAZN. He was with the BBC, Setanta, BoxNation and BT. I think Jimbo has produced more live boxing shows than any producer in history.

Bentley has also made a documentary about Martin and Moss Side. It’s called M14: A Moss Side Story, and it will be shown for the first time on BT on Thursday March 24.

It’s a film of obsession and passion and knowledge. All the main players are there, all telling their story. It’s a journey. Phil Martin, his gym and his fighters is a story worth telling.

by Steve Bunce